This week, the Government announced it's putting 1800 new beds in New Zealand prisons at the cost of $1 billion.

Over half of these will end up being filled by Māori men.

Māori make up only 14.6 percent of New Zealand's population, but a staggering 51 percent of its prison population.

The high number of Māori in prison can be directly linked to the endemic poverty within Māori society, but where does this poverty come from?

Māori Party co-leader Marama Fox told Newshub that inter-generational poverty can be directly linked to the displacement of Maori during the land wars of the 1860s.

"Māori have experienced poverty since colonisation. Legislation forced Māori into poverty in order to acquire land," she said.

"So the taking of land from Māori can be directly linked to the poverty that is creating today's high prison rate."

Historian Vincent O'Malley has extensively researched the land wars (New Zealand Wars), and especially the invasion of the Waikato for his new book The Great War for New Zealand.

He also believes there is a direct link between the land wars and Māori poverty.

"There's no doubt that the invasion of the Waikato impoverished vast numbers of Waikato Māori. Over 1.2 million acres of land was confiscated so huge numbers of Māori are rendered landless overnight, and that carries on for many generations," he told Newshub.

Mr O'Malley has found out that prior to the war the Waikato tribes had a thriving economy, based on feeding Auckland's settler population.

"Auckland newspapers in the 1840s and '50s acknowledged that without Māori bringing them produce and crops every week, they would have starved," he says.

"So that economy is destroyed overnight by the invasion of the Waikato.

"You also have troops who deliberately loot and pillage all of the Māori villages as they go through, so there was kind of a scorched earth tactic involved.

"Crops were destroyed, the economy is obliterated overnight. This does have consequences that last over many generations."

Mr O'Malley says the British government was very reluctant to get involved in a New Zealand war, because of the huge military and financial burden on the British taxpayer.

"Many of the troops increasingly saw the war as a sort of land grab on behalf of New Zealand settlers, from which Britain itself saw no real benefit from at all," he says.

"It was the colonial ministers of New Zealand who were eyeing up these valuable and very lucrative lands in the Waikato district from which settlers had largely been excluded before the war," Mr O'Malley says.

"The Waikato has these extremely valuable grasslands for pasture. That was certainly a strong factor in the decision to invade the Waikato."

The invading force was a mix of British regular soldiers, guerrilla-styled forest rangers, local militia and many Australians.

"There were quite a significant number of Australians were recruited to serve as military settlers, so they would serve for three years and then receive grants of land themselves," says Mr O'Malley.

"They are involved in some of the real contentious incidents in the Waikato war, such as the attack on the main centre of commerce for Māori in the Waikato, which was filled with women, children and the elderly," he added.

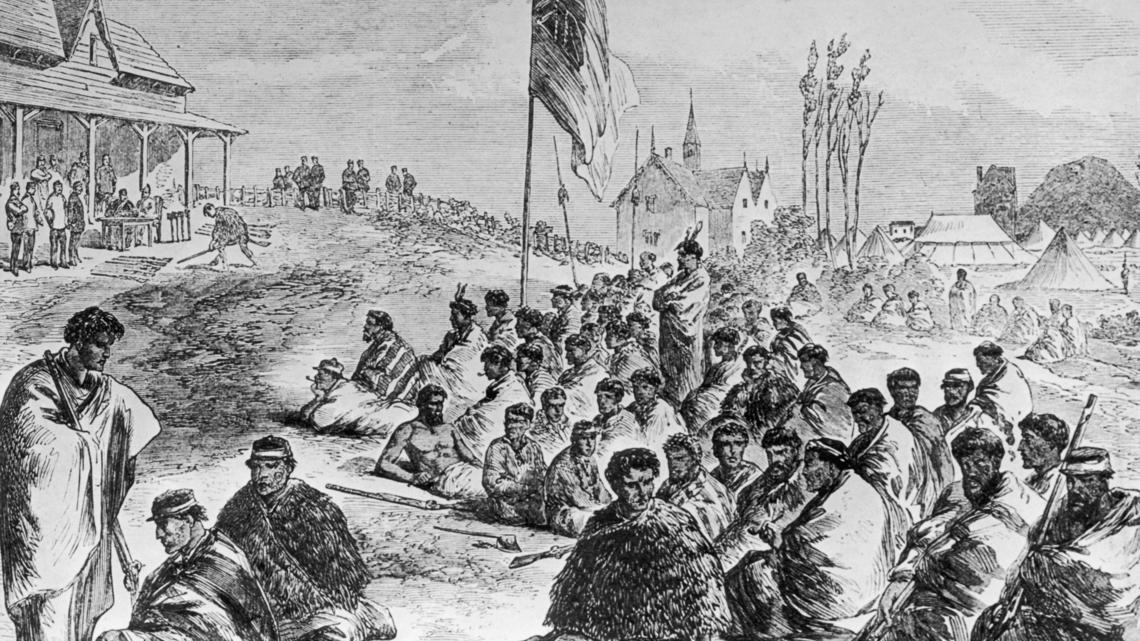

Māori prisoners taken during the New Zealand land wars (Getty)

After the war, the Native Schools Act of 1867 made it illegal to teach Māori in their native language. One Member of Parliament debated: "The time has come to decide whether to exterminate the natives, or to civilise them.

"But if we are to civilise them we have to do so in a language that is more conducive to human thought."

This law stayed in placed until 1969.

Ms Fox told Newshub: "That is generation after generation of cultural genocide. You're not good enough for anything, and if you hear that over and over again, then you live up to the expectation - which is nothing."

"The high numbers in prison stem from poverty and also from injustice from racism in the justice system where Māori have been treated harsher in the system than non-Māori, and this is as evident today as it was in the past."

Māori children were forbidden from speaking te reo at school (Getty)

From once owning all of New Zealand's land, Māori are now virtually landless, owning less than 5 percent of the country's total land mass, and 95 percent of that land is on the East Coast.

Ms Fox says: "It goes deeper than the land wars and the land confiscation, and goes straight to the heart of racial engineering, through assimilation practices. Maori are treated disproportionally within law and within and the education system."

Māori are often perceived as being a violent race, having 'a warrior's mentality'. And this predisposed willingness to use violence often leads them to committing violent crime, and in term ending up in prison.

But were Māori a violent society before they were colonised by Pakeha? The diaries and letters of early settlers describe the Māori family unit as being incredibly peaceful. Fathers nurtured their children with the utmost care and respect.

These first Pakeha settlers saw no marks of violence on Māori women or children. Family violence was not part of Māori law.

"Māori family violence came through the culture of Victorian education where you would use violence to bring children to submission," Ms Fox says.

"In order to get your children to be compliant, in order for your children to be successful in a Pakeha world, you need to punish them into submission.

"Boys were especially treated harshly. I can look at uncles and grandfathers in my family who harshly treated their children, but they thought they were acting appropriately.

"I think there is a direct correlation between the Victorian model of education and child abuse today," she says.

Ms Fox says: "First you need to address the disparities and injustices inside the justice system, where you're three times likely to be arrested for the same crime as non-Māori.

"You're three times as likely to be incarcerated for the same crime as non-Māori, and you're three times as likely to be incarcerated for longer periods for the same crime as non-Māori.

"The Government won't even admit that there is injustice, but they have agreed with the Maori Party, that we can carry out a Government research into the unconscious bias in the justice system."

The Māori Party want to look at rehabilitation rather than arrest and prosecution.

Ms Fox says: "Incarceration makes Māori men stronger abusers, so why not send them through a court process where they undergo family counselling - strengthen the family relationship so it doesn't break apart.

"Our current social system is set up to break families apart. You get more money on the DPB (Domestic Purposes Benefit) than you do on a married benefit," she added.

"If we spent the same energy and money on building relationships and strengthening families where they raise children and loving and nurturing homes, then we add to New Zealand society. And by raising the value of every member rather than incarcerating and producing stronger, harder criminals."

Ms Fox doesn't want 1800 new beds in New Zealand prisons; she believes the beds should be in other places.

"We should have put 1800 beds into residential rehabilitation for drug and alcohol abuse, and specifically P, because there is such limited help out there in the community to address it. We should have put more beds into state care, addressing mental health."

The 1800 new prison beds will inevitably be filled by a new generation of convicted Māori.

They are the end result of a social system that has long stopped working for them.

Newshub.